Epidurals and Spinals for Labor & Birth

Epidurals and spinals are common names for a certain method of pain relief that reduces or blocks pain in the lower half of the body. They are sometimes used during and following surgery, and epidurals are the most common method of relieving labor pain in the United States.

When used during labor, epidurals can often block a significant amount of sensation, but they don’t completely block all sensation. It’s important for laboring women to know that an epidural may give them 70-80% pain relief, but not to expect a guaranteed 90- 100%. Some women find that epidurals aren’t always effective for them. Sometimes, the same woman will have more pain relief with an epidural during their labor with one baby and a different (or less) amount of pain relief with a succeeding baby. Because complete pain relief with an epidural is not guaranteed, spinals are often used as anesthesia during Cesarean surgeries because they will completely block all sensations from mid-back down to the lower section of the body.

Click on the links to take you to the information you would like:

What medications are given in an epidural?

What are the common side effects of epidurals?

What are pros and cons of epidurals?

When can an epidural not be given?

What’s the difference between an epidural and a spinal?

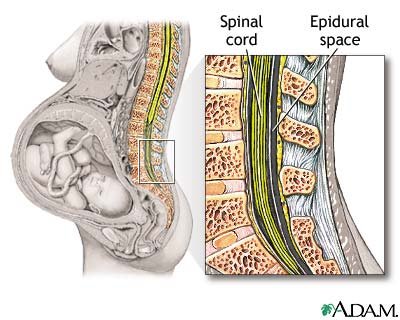

Epidurals work by delivering medication through a tiny tube into the space near the membrane that surrounds your spine. That space is called the epidural space. Since the nerves to your lower body go through this epidural space, medication injected or pumped into this space can block the nerve signals.

To give an epidural, an anesthesiologist or nurse-anesthetist tells the laboring woman to curl up on her left side or to sit on the edge of the bed and lean forward, arching her back. This helps the anesthetist to evaluate the area the needle needs to be injected into. They try to begin the procedure between contractions, but even if a contraction occurs, it is critical that the mother remain extremely still.

Her back will be washed with an antiseptic and then the anesthetist will inject a local anesthetic into the mid-to-lower back to numb it. That injection might sting or burn some, but most women tolerate it well. After the area is numb, the anesthetist will insert a needle into the lower back between the vertebrae into the space between the bones of the spine and the membrane called the dura mater (tough mother). That space is called the epidural space. The anesthetist will then thread a tiny tube (called a catheter) through the needle into the epidural space. The needle is then removed, leaving only the tiny catheter in place.

Medication can then be given through the catheter which is taped to the back to prevent it from slipping out or moving. Once the catheter is secured, a nurse will help the mom get as comfortable as possible. It is usually necessary for the mom to initially lie almost flat on her back (sometimes slightly tilted) to make sure the medication flows where it is needed. After awhile, the woman’s position can be readjusted into a more comfortable position.

A small dose of medication will first be given to make sure the epidural is placed correctly and that there is no negative reaction to the medication. If there are no problems with the test dose, a full dose of medication will be given. Most women begin to feel pain relief within 10-20 minutes after the full dose of medication is given.

Some hospitals give the laboring woman the opportunity to press a button to receive more medication. The medicine pump is set so that only a set amount of medication can be given within a certain amount of time, so the woman cannot overdose herself. If she presses the button, but the maximum dose has already been given, the pump will not release any more medicine, but it will make a noise that sometimes has a positive psychological effect on the woman.

A combination of a narcotic med or opiod (such as morphine or fentanyl) and an anesthetic may be given via the catheter. The anesthetics used may be lidocaine, bupivacaine, chloroprocaine or another medicine.

Be sure to advise your anesthetist if you are allergic to any anesthetics or narcotics, even if you’ve reported that on your forms.

Narcotics may be used to reduce the need for a higher dose of anesthetic. Sometimes a third medication is used to stabilize the mother’s blood pressure.

Common Side Effects of Epidurals

Low blood pressure – the medications affect the nerves going to your blood vessels, so it is common for blood pressure to drop some. Extra IV fluids or drugs can be given to correct this if necessary.

Itching – Some women have this reaction to the narcotic medicines that are often used in combination with the anesthetics. It can usually be treated with medication.

Uncontrollable Shaking – This could be a result of the increase in IV fluids (colder than body temperature) and the vasodilating effect of the epidural. Some women have little or no shaking, but others have teeth-chattering shaking.

Nausea & vomiting – This can occur, but doesn’t seem to be very common.

Difficulty passing urine – The epidural medications affect the nerves to the bladder, so it may be necessary for a nurse to reinsert a bladder catheter after the birth to help empty the bladder.

Headaches – if the fluid that surrounds the spinal cord leaks into the epidural space, it can cause a “spinal headache,” which can be very painful. If pain medication isn’t enough to control the headache pain, a blood patch can often “patch the leak.”

Inadequate pain relief – epidurals may be more or less effective with different women and with different births. If an epidural doesn’t seem to be working, the nurse will call the anesthesiologist to come back and evaluate the situation. If warranted, the anesthesiologist may remove the epidural catheter and insert a new one.

“Walking Epidurals” (Combined Spinal-Epidural or CSE)

For a “walking epidural,” a numbing injection will be given as described above, and then the medication (a narcotic, an anesthetic or a combination) is injected into the space underneath the arachnoid membrane (the intrathecal area). The needle is then pulled back into the epidural space and a catheter is threaded into that area (as in a regular epidural). The needle is removed, the catheter is taped in place, and the laboring woman can often move around a bit more in bed, but she may not be allowed to actually walk because her balance, reaction time and muscle strength will be reduced as long as the medication is effective. CSE’s usually provide pain relief for about 4-8 hours. The laboring woman can request a regular epidural if she feels that she needs a longer-lasting pain relief.

Pros and Cons of Epidural Anesthesia

Helpful Aspects:

If a laboring woman feels that she is too exhausted or too overwhelmed to continue in labor, an epidural can help her rest and feel more positive about the rest of her labor.

If a woman in labor is suffering from pain and cannot relax, an epidural can give her enough pain relief to allow her body to relax and help labor progress.

If a woman in labor has preeclampsia or high blood pressure, an epidural can help lower blood pressure.

Epidurals allow the mother to be alert during the remainder of her labor and birth of her baby, whereas narcotics (given by mouth or injection) often make the mother very groggy and are more likely to negatively affect the baby.

Possible Problems:

Epidurals may cause a sudden drop in blood pressure, which decreases the blood flow and oxygen to the baby. It can make the mother feel dizzy and nauseated. Because of that risk, the woman’s blood pressure will be checked frequently, and she may have to receive additional medications, oxygen and IV fluids to correct the problem.

Lying in one position can slow the progress of labor and some studies indicate that it may prevent the baby from rotating easily during labor, increasing the possibility of needing forceps or a vacuum extractor at birth or a Cesarean surgery.

Some women experience ringing in their ears, shivering, nausea, soreness or a backache where the needle was inserted (even for weeks after the birth) and difficulty urinating. Some women also experience a severe headache due to leakage of spinal fluid if the needle was inserted too deeply. (An injection of her own blood into the epidural space often corrects the headache immediately. That is commonly called a “blood patch.”)

Epidurals often slow the process of labor, making the use of pitocin necessary.

For some women and for various reasons, the epidural doesn’t always work. Because the catheter is in place and because of the potential effects of the medications used, the laboring woman has to remain in bed, lying in a reclining position or on her side, and must now cope with contractions without the benefit of standing, walking, rocking, bouncing or other movements for pain relief.

Some women experience difficulty pushing with their contractions, making forceps, vacuum extractor, pitocin or a Cesarean section necessary.

Some women may experience numbness in the lower half of their body for several hours after birth. (Numbness usually wears off within 1-2 hours after birth.)

Rarely, permanent nerve damage can result in the area the needle was inserted.

Some research shows an increase risk for heart rate variations in the preborn baby, and an increased risk that the newborn may have more trouble breathing after birth. Some research studies are showing an increased tendency for breastfeeding problems among newborns whose mothers received epidural medication during labor. More research is being done in that area to try to determine cause & effect.

When an Epidural May Not be an Option

It’s also important to know that epidurals may not always be an option. There are occasions when an epidural cannot be administered. Blood work will be taken and analyzed before the epidural is given.

If the mother’s platelet count is low or if she has an infection, an epidural may not be an option. If she uses blood thinners or has a skin infection on her back, she may not be able to use an epidural. Scoliosis can sometimes make epidurals more difficult to administer.

Epidurals are sometimes not given until the mother’s cervix is at least 4 cm dilated or less than 8 cm dilated.Those guidelines can vary from doctor to doctor. There are other things that can make an epidural too risky to be considered safe for the mother or baby. It is wise to discuss all of these things with an obstetrician or midwife prior to labor and birth.

Differences between Epidural and Spinal Anesthesia

With spinal anesthesia, the anesthetic is injected past the epidural space and into the space called the subarachnoid space which is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Spinals usually involve one injection and completely anesthetizes that area for a certain amount of time. This makes it a commonly used method of anesthesia for C-sections. With a spinal, the anesthetic effect usually takes place within 5 minutes, whereas an epidural may take 10-20 minutes to take effect. The epidural space is larger, therefore a larger initial dose of medication can be given with epidural anesthesia. Also, a catheter is left in place with an epidural, so a continuous drip of medication can be given.

I hope this has answered many of your questions about epidural analgesia and spinal anesthesia for labor and birth. If you are interested in learning more about using this type of medication for your birth, check with your local hospital for epidural classes. Also, be sure to educate yourself as much as possible, so you can make an informed choice.

How does an epidural work?

How does an epidural work?